India may be celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the 1965 war this month but it will need a lot more than a "war carnival" at Rajpath to etch it in public memory. If 1965 is truly India's forgotten war, there are reasons for it.

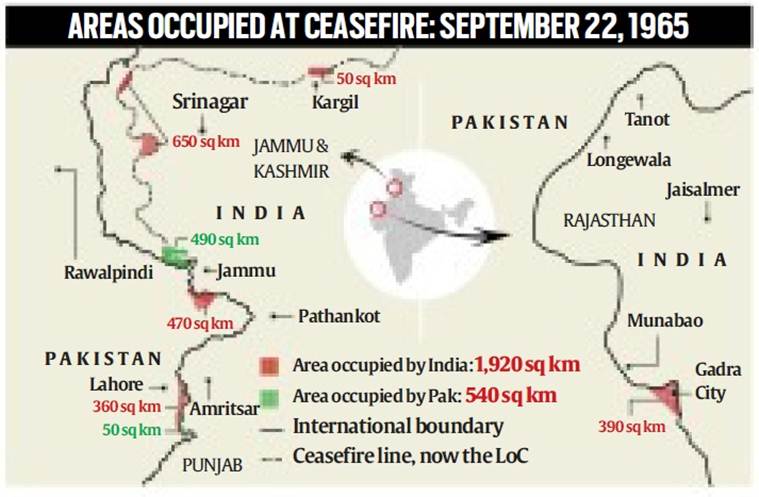

Sandwiched between the humiliation suffered at the hands of the Chinese in 1962 and the exhilaration of a Pakistani surrender in 1971, the 1965 war resulted in a stalemate. There were no surrender ceremonies at Dhaka's Race Course Ground like in 1971 nor was there an emotional "Ae mere watan ke logon…" which brought Jawaharlal Nehru to tears like in 1962. 1965 didn't change the political geography of the sub-continent; no territories exchanged hands. Before the ink on the Tashkent Agreement had dried, then prime minister Lal Bahadur Shastri passed away, overshadowing everything that had happened earlier.

The war was the product of a certain geopolitical and temporal context. The Indian Army had lost badly to the Chinese in 1962, which created a sense of false superiority in the Pakistan army. Hoping to squeeze India with Chinese support, Pakistan had ceded land in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir to China. As a member of various Western military alliances, Pakistan had also benefited from American aid and military equipment. Pakistan was politically stable and its economy was held up by top economists as an example for other developing countries.

READ: Key Battles – Memorials, war stories keep Asal Uttar alive

Ayub Khan's belief that "Hindu morale would not stand more than a couple of hard blows at the right time and place" was emboldened by his army's performance during the limited conflict in the Rann of Kutch in April 1965. The award of the international Kutch Tribunal had given 350 sq km territory to Pakistan and put Shastri under pressure.

Meanwhile, India was still in the process of strengthening and modernising its armed forces following the 1962 debacle and 1965 seemed like an opportune time for Pakistan to move in. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Ayub's young and ambitious foreign minister, had been speaking of an Algeria like uprising in Kashmir which would finish "the unfinished business of Partition". Bhutto was the brain behind Operation Gibraltar, where Pakistan aimed to stage an insurrection in J&K through massive infiltration, sabotage and subversion.

Rudra Chaudhuri, senior lecturer at King's College, London, says, "This was Bhutto's war — an opportunity seized by a relatively young and ambitious actor working behind the scenes. The Kashmir cell, led by those drawn to this maverick, convinced Ayub Khan of the potential for rebellion in Kashmir."

But, Chaudhuri adds, "Neither Bhutto nor Ayub imagined the outbreak of war. Hypnotised into believing that rebellion in Kashmir supported by the Pakistani army would lead to the overthrow of Indian rule, Ayub and his army chief, General Musa Khan, were dumbstruck when India opened a second front."

That second front was in Punjab. After the failure of Operation Gibraltar, Pakistan launched Operation Grand Slam to capture Jammu and isolate Srinagar from the rest of India. Shastri decided to escalate the war across the international border taking Pakistan by surprise. Worried about the Chinese threat, India did not target East Pakistan.

The 1965 war ended in 22 days, when General J N Chaudhuri mistakenly assumed that the army was running out of ammunition and had suffered considerable tank losses. He advised Shastri to agree to a ceasefire even though the prime minister wanted to prolong the war by a few days if India could win a spectacular victory.

For India, there were many high points of the war. Indians, despite their less sophisticated equipment, performed better than the Pakistanis. Pakistani tanks met with disaster in the battlefields of Asal Uttar and Phillora. India's offensive thrust in Kashmir led to the capture of the strategically important Haji Pir Pass and some tactically crucial heights in Kargil. In Punjab, the army reached close to the outskirts of Lahore but did not press on. India, however, suffered from poor military leadership, flawed intelligence assessment and a rather poor strategy of delivering a large number of inconsequential jabs instead of deep, powerful thrusts inside Pakistani territory.

The Indian Navy didn't participate in the war and the performance of the IAF was mixed. Pushpindar Singh, author of IAF's three-volume official history, Himalayan Eagles, says, "The first air war in the sub-continent was at best a draw. The smaller in size Pakistan Air Force certainly did better in the opening rounds but towards the end, the Indian Air Force gradually got its act together and was increasingly dominant at time of the ceasefire".

According to then defence minister Y B Chavan's War Diary, published by his aide R D Pradhan, Chavan gave the Army and the IAF the go-ahead to launch attacks across the ceasefire line (now the LoC) without consulting the Emergency Committee of the Cabinet. This account is corroborated by the then defence secretary PVR Rao and army chief General Chaudhuri.

The 1965 war also set the template for political control of the military during wars. As historian Srinath Raghavan says, "The principal lesson drawn by political and military leaders from the debacle of 1962 was to give the military a free hand in operational matters. Hence, in 1965, the politicians consciously refrained from enquiring too deeply into the actual conduct of war. This lack of adequate civilian oversight was one reason why India did not achieve a better outcome. The 'victory' in 1965 also cemented the notion that this was the best way to conduct civil-military relations, an assumption that prevails to date."

Politically, it was a tough time for Shastri. He had sent a strong message by refusing to restrict the war to J&K. Before leaving for Tashkent, he had publicly announced that he would never return Haji Pir Pass. But, as former ambassador to Pakistan K S Bajpai, who was part of the Indian delegation at Tashkent, says, "I don't know how we convinced ourselves to sign on what we did when Shastriji remained opposed to giving Haji Pir back. The pressure of Soviets not using a veto at the Security Council on Kashmir may have done the trick."

"In the end, Pakistan as a nation achieved little," says Chaudhuri. India did slightly better even though the military gains were lost at the diplomatic table.

War diary: Start to finish

May 1964

Trouble in Kanjarkot, Rann of Kutch, as Pakistani trespassing increases. More incidents by Jan-Feb 1965

February-April 1965

India's 31 Infantry Brigade instructed to capture Kanjarkot in Operation Kabaddi. Pakistan retaliates, launches Desert Hawk II. Raiding party of 6 Punjab (Pakistan) kills eight Indians.

April-June

Ceasefire negotiations begin. Both sides agree to restore status quo as of January 1, 1965. Ceasefire signed. Is to take effect from July 1.

June

Indian military authorities, prompted by ceasefire violations in J&K, decide not to remain passive any longer. Launch offensive.

August 5

Pakistan's 12 Infantry Division, led by Maj Gen Akhtar Hussain Malik, launches extensive infiltration. Under Operation Gibraltar, 30,000 men are pushed across the ceasefire line (now called LoC) into J&K.

August

Indian leadership decides Pakistan needs to be dealt with strongly. India's 68 Infantry Brigade is tasked to capture Haji Pir Pass in operation codenamed "Bakshi". Haji Pir sector is secured. India's XI Corps and I Corps plan offensive in Lahore and Sialkot. Offensive called off due to ceasefire on the night of September 23.

September 1

Pakistan makes a three-pronged attack. At 3 pm, Brigadier Manmohan Singh, commander of 191 Brigade Group, calls for IAF support when Pakistani tanks have reached 450 metres from Brigade HQ. IAF support arrives at 5 pm and bombs Pakistan army's gun posts causing damage to all artillery ammunition lorries, tank ammunition. Brigade HQ is moved to Jaurian and given responsibility of defence of Akhnoor.

September 2

Pakistan Sabre jets bomb Jaurian in Jammu but despite initial success and closing in on Akhnoor, Pakistan's Grand Slam loses momentum. Then, Pakistan carries out air raid on Amritsar.

September 4

UN Security Council adopts a resolution jointly sponsored by six non permanent members for immediate ceasefire in Kashmir. Indian PM Lal Bahadur Shastri blames Pakistan for situation in J&K.

September 10

Pakistan's famed Patton tanks launch a tank offensive on Manawan in Khemkaran sector. A recoilless gun mounted by Havaldar Abdul Hamid knocks out three Patton tanks. Hamid is posthumously awarded Param Vir Chakra.

September 16

Shastri makes a statement in Parliament, puts blame on Pakistan.

September 22

Bhutto makes an impassioned statement on Kashmir at UNSC emergency session. Reads out Ayub Khan's statement that Pakistan is unsatisfied with ceasefire… India's permanent representative to UN, G Parthasarathi, conveys that India has accepted ceasefire and asks for a new date to implement it. UNSC fixes it at 3.30 pm on September 23

September 23

Guns go silent.

January 4, 1966

Indian and Pakistani leaders meet in Tashkent, Soviet Union, for talks

January 10

Shastri and Ayub Khan reach a final agreement. Joint declaration is signed by 4.30 pm.

January 11

Shastri dies of heart attack at 1.30 am.

(Compiled by Pranav Kulkarni)

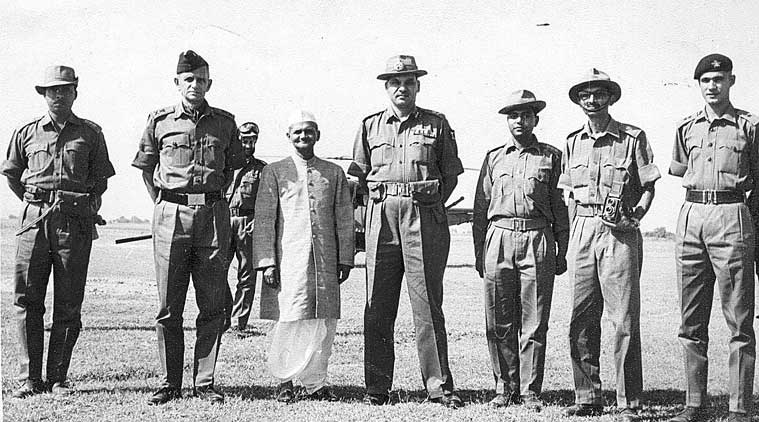

They were at the forefront

Capt Amarinder Singh

Sikh Regiment, former ADC to GOC-in-C Western Command Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh in 1965

"For me, it was a great opportunity as a youngster to be with Army Commander, Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, who was commanding the entire Western Army which was at war. I saw the Commander at work and not once did I see him stressed. He didn't show any signs of panic in the worst of conditions, and this (confidence) spread (across the regiment) and that is why the Army did so well."

***

K S Bajpai

former ambassador to Pakistan (1976-80), who was posted in Karachi during the 1965 war

It is definitely a time to introspect. We may have been successful in stopping Pakistan's misadventure for the time being in 1965, but we have not managed to leave a lasting impact on them. Pakistan's determination to wrest Kashmir from us, by any means, fair or foul, still exists. So, measures to tackle such stance must be a part of our policy.

***

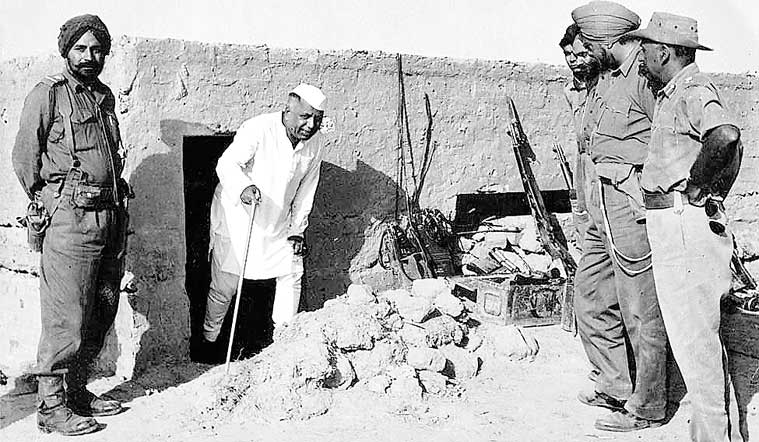

Kuldeep Nayar

veteran journalist who, in his book Beyond The Lines – An Autobiography, has chronicled the 1965 conflict

"The 1965 war at best was a draw or just a small edge over Pakistan. Lahore was important but we did have to bypass it. We are boasting too much. We could not avoid it…(Many years ago) I wanted to talk to Ayub Khan, Pakistan's president then. He said I should talk to (Zulfikar Ali) Bhutto as it was his war. When I met Bhutto, he said, 'I had really thought that if Pakistan could beat India, this is the time. I was wrong….'"

***

Capt Reet MP Singh (Retd)

8 Cavalry, awarded Vir Chakra for the 1965 war

"I consider myself lucky that I participated in the entire war. It was providence that I was not injured in the beginning of the war and suffered injuries only at the fag end when my regiment was trying to re-capture the village of Mchhike in Khemkaran sector from the Pakistani Army."

***

Lt Col Nagindar Singh (Retd)

3 Cavalry, fought the 1965 battle

"The bulk of my regiment was deployed in Khemkaran sector in the Battle of Asal Utar while one squadron was near Attari to prevent a flanking Pakistani attack. The morale was high. Troops under my command shot down a Patton tank as it came down the Lahore-Amritsar road and we never saw any Pattons again

in that area".

(Compiled by Pranav Kulkarni)

- See more at: http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/big-picture-1965-fifty-years-later/#sthash.ID13lOSi.dpuf